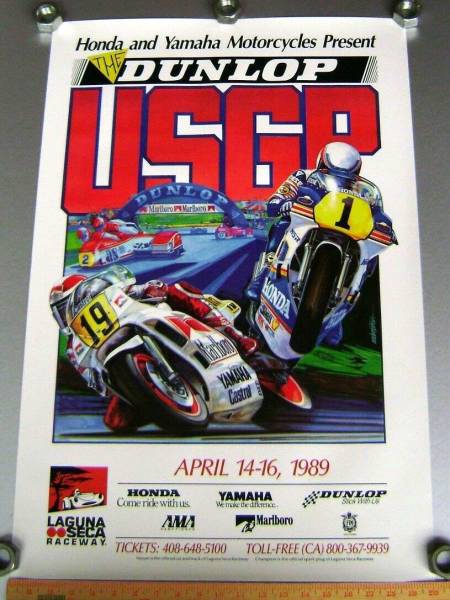

1989 LAGUNA SECA: The Worst USGP Ever

by Dean Adams

Monday, March 18, 2024

You’ll never convince anyone with an intimate knowledge in racing that motorcycle roadracing is a safe sport. Even on the safest track, with a cautious rider wearing the best safety equipment, a life or a career can be extinguished in little more than a heartbeat when factors go wrong. It’s easy to be swayed and believe that because modern bikes and safety equipment are so good and track safety—while still not where anyone would like it—has never been better, that the likelihood of a fatal or career-ending crash is remote, it’s simply not the case. As history continues to show us, an amazing rider can be crippled—or worse—in an instant. The 1989 US Grand Prix at Laguna Seca proved it.

The 1989 USGP at Laguna Seca was an event marred by tragedy; it left the 500 grid in shambles, with at least three riders in the hospital—one in a coma—and it went a long way towards killing the popularity of GP racing in America. The ’89 event is still a low point for those who were there that day. Even the rider who won the premier race that day probably wishes the race had never happened.

International Grand Prix roadracing made a glorious return to America in 1988, with packed hills and grandstands resonating with love for motorcycle racing. Californian Eddie Lawson won the event in front of an adoring audience. Supporters of the event hoped that the USGP celebration would continue for years to come with even more fans and appreciation for the 170-horsepower two-stroke missiles; but all that was sucker-punched in 1989. The USGP never regained its momentum, and the event just trickled away, with fewer and fewer fans attending each year.

Before his career-ending crash and resulting paralysis in 1993, there was but one tragedy in Wayne Rainey’s professional racing career—the 1989 USGP at Laguna Seca Raceway. Even though Rainey won that race in front of friends and family, mulling the event—even years later—only made him shudder, when he remembered what transpired.

Doomed From The Start

The 1989 USGP was, in retrospect, doomed from the start. The 1989 Grand Prix series featured an amazingly aggressive schedule—it listed a Grand Prix at Phillip Island on April 9, and the USGP on the very next weekend—April 16, meaning that the entire GP circus would have to get their men and machines from one hemisphere to the next and be ready to start practice in just five days time. Even in those pre-9/11 days, when customs officers would help a racer in need if you found the right one, shipping planeloads of crates from Sydney to San Francisco and having them out of customs and at the track in five days was an impossible goal.

It was no surprise to anyone with knowledge in international shipping that the crated GP bikes were late in arriving in the US and slow to be released by Customs (although an airport labor dispute in Australia started the sluggishness). Many of the GP machines didn’t even arrive at Laguna Seca until Friday morning. Crates of parts and pallets of fuel trickled in all weekend long. And so 500 practice was blown off for most of Friday.

It was no surprise to anyone with knowledge in international shipping that the crated GP bikes were late in arriving in the US and slow to be released by Customs (although an airport labor dispute in Australia started the sluggishness). Many of the GP machines didn’t even arrive at Laguna Seca until Friday morning. Crates of parts and pallets of fuel trickled in all weekend long. And so 500 practice was blown off for most of Friday.

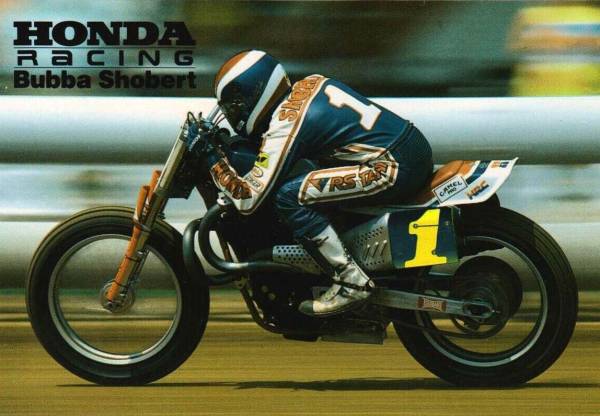

Clearly, the 1989 USGP lashed out and backhanded American Bubba Shobert the hardest. He would never again race after the afternoon of April 16. But even without Shobert’s tragic incident, the field was littered by riders and teams that would have preferred to forget that race altogether.

By Sunday afternoon, after the last race of the weekend, the Grand Prix series lay decimated by injuries. Chief among them: 1987 world champion Wayne Gardner, mounted on an NSR500 V-4 Honda. Gardner was the gnarliest Australian rider of the era, well-known for his beyond aggressive riding (especially in light of the period, when a nasty 500 with a light-switch torque curve on Michelin tires regularly tossed riders fifteen feet in the air in typical highside crashes.) Even with the abbreviated practice schedule at Laguna, Gardner found time to crash no less than five times, including his race crash, which broke his left leg in two places.

Not When Will It Stop. If It Will Stop

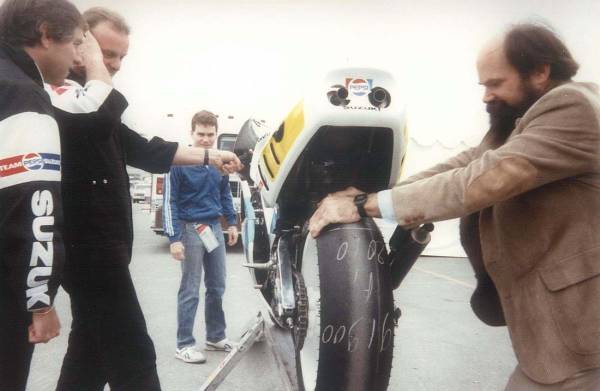

In 1989 at Laguna Seca, the 500cc class faced significant challenges due to brake issues, particularly with the introduction of carbon fiber brakes. Many of the Honda bikes experienced overpowering of their steel discs within just a few laps, highlighting the transition phase as teams adapted to the new carbon disc technology. Honda riders found themselves switching between bikes equipped with steel brakes, which struggled to provide adequate stopping power, and those equipped with carbon discs. The carbon brakes proved formidable once properly heated, delivering stopping power that seemed almost divine, gripping the track with a force that captivated onlookers. This period of experimentation and adaptation added an intriguing element to the racing spectacle.

Gardner, who should be commended for his never-say-die attitude, was not alone in having only bad things to write on postcards sent home from Laguna. Eddie Lawson won the 1988 USGP in dramatic fashion, showing that the hot set-up at Laguna was a tight line, a docile bike and track knowledge. In 1989, he only had track knowledge to defend himself with. The off-season switch from Agostini Yamaha to Kanemoto Honda put him on a vicious NSR500—a bike that didn’t steer well and had a powerband made for Hockenheim’s long straights, not Laguna Seca’s twisty terrain.

Spectator crowds in 1989 were well down from the 100,000 at Laguna Seca in 1988. While the field was actually more competitive in 1989 than it was in 1988, fewer spectators came to the event. Assuredly, many of them felt burned by the high ticket prices, lengthy lines no one had seemed to plan for and the excruciating four-hour wait to exit the track they’d experienced in 1988. One could attribute the attendance problem to any number of factors, but it remains conventional wisdom in US motorcycle racing that poor event management and unfriendly riders (several Euro-GP stars of the era walked right past autograph seekers when leaving the track) will kill an event like a silver bullet shot into a werewolf.

Countdown To Infamy

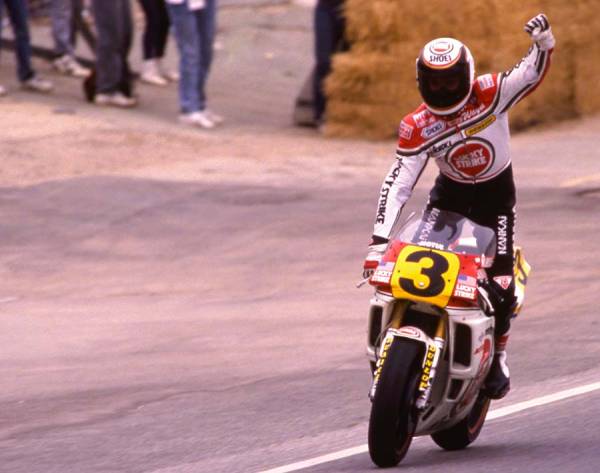

The ’89 500 event itself was a decent race, at least initially with Lucky Strike Roberts-mounted Wayne Rainey showing what was to come at future USGPs he raced in. Rainey threw down an unmatchable lap for pole in qualifying, and in the race pulled a textbook Rainey—lapping so fast at the front that no one could hang with him. Texan Kevin Schwantz on the Pepsi Suzuki actually led for a brief moment (as did Honda-mounted Eddie Lawson), but Rainey went to the front and his pace was devastating.

Schwantz finished second at Laguna, showing he did indeed have the perseverance to finish and not win when circumstances demanded it, although that was not his early reputation. Schwantz had started the 1989 season with great hopes of winning the 500 title—he won the Japanese Grand Prix opener—but a fiendish lap one highside the week before in Australia knocked him out of the race.

The circumstances of, and the brawl over, third place eventually branded 1989 as the worst USGP ever. Late in the race, Rainey was out front, having almost effortlessly left the pack. Schwantz owned second place comfortably.

Third place, though, was a different matter, as three or four riders disputed the position for most of the race: Kevin Magee on the second Roberts Lucky Strike Yamaha, Lawson on the Kanemoto NSR Honda, Gardner on the factory NSR and even a distant Niall Mackienzie on the second Agostini Marlboro Yamaha.

Gardner left the fight for third in an ambulance after a wicked lap ten crash. Anyone who has tried to break a green tree branch in half can imagine what Gardner’s femur looked like post-crash, with the bone broken and twisted in two.

Lawson had third place by the halfway mark, but even the steady one started to ride wide in corners when the piggish Honda’s chassis and brakes wheezed. You can’t ride anything but the precise inside racing line at Laguna and expect to do well. Lawson’s uncharacteristic wide line eventually let Australian Kevin Magee past, and with just a few laps left in the race, Magee appeared to have third place under his belt and an all-American podium was off the books.

Rainey rode a red-hot pace at the front, and the riders behind him pushed hard as well—so hard that they were lapping into the back half of the top ten as the laps slipped away.

Just one lap from the end, with Lawson behind him, watching, stalking, Magee’s Yamaha began to burble and pop, his fuel supply diminished. The Yamaha never ran out of gas, but it starved for fuel as the remaining pints in the tank splashed away from the petcock. The fraction of a second that Lawson needed to pass Magee appeared with a Christmas bow on it. He didn’t waste a tenth of a second passing the Yamaha and cementing third place. Rainey won the race—his first-ever USGP win, Kevin Schwantz was second and Eddie Lawson third. The all-Yankee podium actually would have happened, if what followed on the cool-off lap hadn’t.

Magee was enraged that his Yamaha had let him down and run low on fuel. Thus, on the cool-off lap, Magee stopped his machine in the middle of the racetrack to do several long, billowing brake-lock burnouts, taking out some of his frustration on his rear Dunlop slick.

Carnage

Kevin Magee did two or three burnouts in the turn five/six area of the track on the cool-off lap of the 1989 USGP, each a little longer than the previous. Magee parked almost dead-center on the track when doing so. Smoke billowed off the Dunlop and gave the backside of the track sort of a fog at dawn appearance. At the same time, inexplicably, after the aforementioned lapping and then post-race shuffle, third-place finisher Eddie Lawson had finished the race riding next to Bubba Shobert on the cool-off lap. They obviously weren’t racing, and were in fact sitting up, but after a guy has been racing at 170mph and his body is vibrating from adrenaline overload, even 100mph on the cool-off lap seems pathetically slow.

Shobert had just scored the best finish of his young GP season. He’d moved from Texas to Monterey and performed well in front of not just fans, but people who might have been his neighbors. He had a lot to be happy about, and not just for his own sake—his best friend, the man who he had stood with as best man at his wedding, Wayne Rainey, had won the race.

At some point, as Lawson and Shobert, side by side, rode up the track and through the wisps of smoke from Magee’s burnouts, Both old dirt trackers, Shobert looked right over at Lawson, their eyes met through the visors and they smiled at each other. “He sort of motioned to me, with three fingers, asking if I finished third. I nodded yes and put up three fingers,” remembers Lawson. “He was happy and he gave me the thumbs up and grabbed a big handful of throttle.” They were, naturally, near the center of the track, not far off the racing line.

At the last nana-second, out of the corner of his eye, Lawson saw something solid in front of them and he quickly counter-steered, slamming the clip-ons left to quickly swerve right. He narrowly missed Kevin Magee’s still smoke-spewing Yamaha.

Shobert was not as lucky.

Shobert’s Honda hit the back and side of Magee’s Yamaha at full impact; there wasn’t even a moment for Shobert to grab the brakes. “He was still looking at me until the last moment,” recalls Lawson today. “I don’t think he ever saw Magee’s bike through the smoke.”

Shobert torpedoed Magee’s machine and the two went careening up the track, bodies and bikes tumbling and sliding in a sickening scene. What moments before looked like a typical foggy morning in Northern California now looked like the morning-after scene from the film Platoon. People were screaming, tire smoke wisped in the air and smashed motorcycles and parts littered the area.

Lawson succinctly describes the post-incident scene: “It looked like a plane had crashed.”

Shobert lay motionless on the ground. Magee had tumbled off his bike but he crawled up, pulled off his helmet and walked back to the scene, limping badly from a now broken ankle.

Lawson rode off the track after the incident. He hoped Shobert might get up and need a ride back but knew in his gut what he had narrowly missed was bad, thus he slowed his Honda to walking speed and then quickly killed the engine and simultaneously dropped the bike on the ground. He sprinted back to the scene, his pace quickening as the horror he saw through his face shield came in focus.

Shobert lay face-down on the ground, unresponsive. His breathing was erratic and his color darkening. Lawson thought that perhaps the chin strap on Shobert’s Bell helmet was preventing him from breathing, and with the ambulance was still in turn two, he reached in and very carefully undid the strap, being implicitly careful not to move the Texan’s head or neck. Cornerworkers, fans and riders walked among the debris as ambulance sirens wailed on their way to the scene.

Kevin Magee stood in the middle of it all, fat tears streaming down his face; he tried to walk, hobbled by a now broken ankle. He would miss three Grand Prixs because of the injury and finish fifth in the world championship that season.

Bubba Shobert suffered major head injuries in the crash and would never professionally race again. He recovered well from the incident—he now leads a normal life, is re-married and has two children.

Even years later Wayne Rainey can not remember the 1989 USGP for his breakthrough win at the racetrack near his home and closer to his heart. He confessed several times that if he ever lets his mind wander to the 1989 event, his first thoughts were not of his win, but of the tragedy involving his friend Bubba Shobert.

A year or so after the incident Shobert told me that he had no feelings of resentment for Magee or what had happened. He said that in the racing life some risks are accepted no matter how unfair they might seem after the fact.

Be that as it may, some members of the American contingent in Grand Prix didn’t let the incident simply drift away. Later Kevin Schwantz was teamed with Magee at Suzuki and he kept him at arms length the entire time. He wasnt unfriendly, but just did what the team expected him to do—smile for the photographer guys—and little more.

Kevin Magee and Eddie Lawson were involved in several on-track incidents that season and after one such episode, Lawson made his feelings clear on Magee’s ability to control a racing motorcycle, and his judgment in doing so. Lawson said Magee accused him of really being angry over the Shobert incident. “I told him no, ‘it’s just that you’re an idiot.”

“I’ll never understand why he chose to do that right in the middle of the racetrack,” Lawson said.

The USGP didn’t return to America in 1990.

ENDS

ENDS

How was Rainey able to run lap record pace in the race--he lapped into the top ten--without running out of fuel while Kevin Magee's nearly-identical Lucky Strike Yamaha was running low on fuel three laps from the end? Rainey credits mechanic Mike Sinclair's jetting.

"The 1989 YZR500 jetting was critical for the way I rode the bike that year, especially at Laguna Seca," Rainey explained via text message. "The initial throttle opening was key. It was critical for engine response at maximum pressure from the engine at whatever RPM it happened to be at ... plus, the pressure on the chassis and tires and how I applied the throttle with all those factors played an important role in producing fuel mileage to get me to the checkered flag and on two wheels. My bike surged at the top of the Corkscrew on the last lap." (Engines will surge when running very low on fuel when the air/fuel mixture is mostly air.)

Lawson was fined 500 Swiss francs by the FIM for missing the podium. Yes, really. He refused to pay it.

"I was teamed with him (at Suzuki) and I was a good teammate. I collaborated with him and did what was best for the team," Kevin Schwantz says of Kevin Magee. "But I didn't go out of my way to be overly friendly towards him. What he did was about the dumbest f*cking thing I've ever seen someone do on a cool-off lap in a race. It finished Bubba's career."

The 1989 500cc race at Laguna Seca was forty laps long. 40.

Bubba Shobert wore a Bell helmet in the 1989 Laguna USGP. In the two previous Grand Prix races he obviously wore an Arai helmet with a Bell stickers on it.

If you have photos from the 1989 USGP at Laguna Seca, send them here: superbikeplanet@gmail.com

The 1989 USGP at Laguna Seca was an event marred by tragedy; it left the 500 grid in shambles, with at least three riders in the hospital—one in a coma—and it went a long way towards killing the popularity of GP racing in America. The ’89 event is still a low point for those who were there that day. Even the rider who won the premier race that day probably wishes the race had never happened.

International Grand Prix roadracing made a glorious return to America in 1988, with packed hills and grandstands resonating with love for motorcycle racing. Californian Eddie Lawson won the event in front of an adoring audience. Supporters of the event hoped that the USGP celebration would continue for years to come with even more fans and appreciation for the 170-horsepower two-stroke missiles; but all that was sucker-punched in 1989. The USGP never regained its momentum, and the event just trickled away, with fewer and fewer fans attending each year.

Before his career-ending crash and resulting paralysis in 1993, there was but one tragedy in Wayne Rainey’s professional racing career—the 1989 USGP at Laguna Seca Raceway. Even though Rainey won that race in front of friends and family, mulling the event—even years later—only made him shudder, when he remembered what transpired.

Doomed From The Start

The 1989 USGP was, in retrospect, doomed from the start. The 1989 Grand Prix series featured an amazingly aggressive schedule—it listed a Grand Prix at Phillip Island on April 9, and the USGP on the very next weekend—April 16, meaning that the entire GP circus would have to get their men and machines from one hemisphere to the next and be ready to start practice in just five days time. Even in those pre-9/11 days, when customs officers would help a racer in need if you found the right one, shipping planeloads of crates from Sydney to San Francisco and having them out of customs and at the track in five days was an impossible goal.

thanks, Laguna Seca Raceway

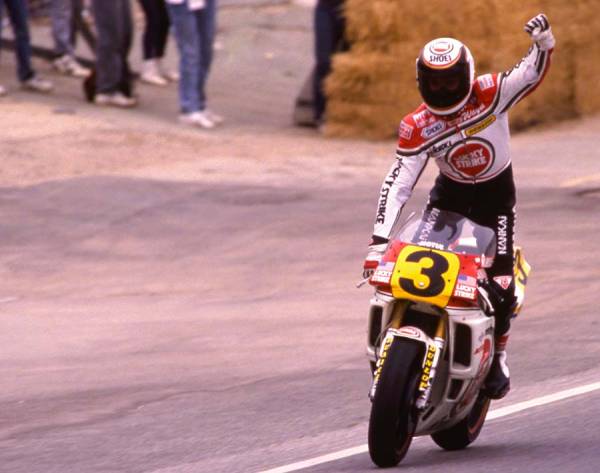

Wayne Rainey took no prisoners at Laguna Seca in 1989. He ran into a lot of problems in traffic in the race WHEN HE LAPPED THE ENTIRE FIELD UP TO SEVENTH PLACE.

Clearly, the 1989 USGP lashed out and backhanded American Bubba Shobert the hardest. He would never again race after the afternoon of April 16. But even without Shobert’s tragic incident, the field was littered by riders and teams that would have preferred to forget that race altogether.

By Sunday afternoon, after the last race of the weekend, the Grand Prix series lay decimated by injuries. Chief among them: 1987 world champion Wayne Gardner, mounted on an NSR500 V-4 Honda. Gardner was the gnarliest Australian rider of the era, well-known for his beyond aggressive riding (especially in light of the period, when a nasty 500 with a light-switch torque curve on Michelin tires regularly tossed riders fifteen feet in the air in typical highside crashes.) Even with the abbreviated practice schedule at Laguna, Gardner found time to crash no less than five times, including his race crash, which broke his left leg in two places.

Not When Will It Stop. If It Will Stop

In 1989 at Laguna Seca, the 500cc class faced significant challenges due to brake issues, particularly with the introduction of carbon fiber brakes. Many of the Honda bikes experienced overpowering of their steel discs within just a few laps, highlighting the transition phase as teams adapted to the new carbon disc technology. Honda riders found themselves switching between bikes equipped with steel brakes, which struggled to provide adequate stopping power, and those equipped with carbon discs. The carbon brakes proved formidable once properly heated, delivering stopping power that seemed almost divine, gripping the track with a force that captivated onlookers. This period of experimentation and adaptation added an intriguing element to the racing spectacle.

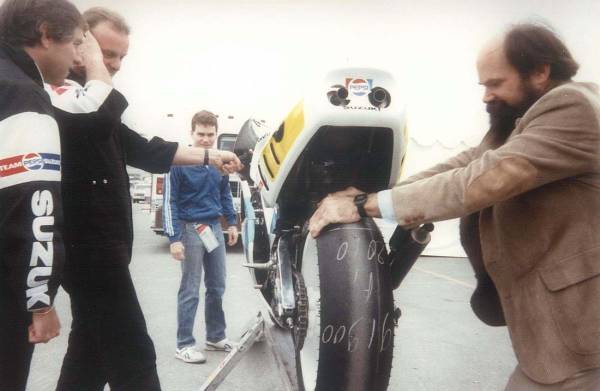

File Photo

Kevin Cameron was the Grand Prix tech inspector for the 1989 USGP. You'd be surprised to hear what he found on some of the 250s in terms of stuff that would get your bike failed at a CRA club-level technical inspection.

Gardner, who should be commended for his never-say-die attitude, was not alone in having only bad things to write on postcards sent home from Laguna. Eddie Lawson won the 1988 USGP in dramatic fashion, showing that the hot set-up at Laguna was a tight line, a docile bike and track knowledge. In 1989, he only had track knowledge to defend himself with. The off-season switch from Agostini Yamaha to Kanemoto Honda put him on a vicious NSR500—a bike that didn’t steer well and had a powerband made for Hockenheim’s long straights, not Laguna Seca’s twisty terrain.

Spectator crowds in 1989 were well down from the 100,000 at Laguna Seca in 1988. While the field was actually more competitive in 1989 than it was in 1988, fewer spectators came to the event. Assuredly, many of them felt burned by the high ticket prices, lengthy lines no one had seemed to plan for and the excruciating four-hour wait to exit the track they’d experienced in 1988. One could attribute the attendance problem to any number of factors, but it remains conventional wisdom in US motorcycle racing that poor event management and unfriendly riders (several Euro-GP stars of the era walked right past autograph seekers when leaving the track) will kill an event like a silver bullet shot into a werewolf.

Countdown To Infamy

The ’89 500 event itself was a decent race, at least initially with Lucky Strike Roberts-mounted Wayne Rainey showing what was to come at future USGPs he raced in. Rainey threw down an unmatchable lap for pole in qualifying, and in the race pulled a textbook Rainey—lapping so fast at the front that no one could hang with him. Texan Kevin Schwantz on the Pepsi Suzuki actually led for a brief moment (as did Honda-mounted Eddie Lawson), but Rainey went to the front and his pace was devastating.

Schwantz finished second at Laguna, showing he did indeed have the perseverance to finish and not win when circumstances demanded it, although that was not his early reputation. Schwantz had started the 1989 season with great hopes of winning the 500 title—he won the Japanese Grand Prix opener—but a fiendish lap one highside the week before in Australia knocked him out of the race.

Hanoi Henny

Eddie Lawson finished third in the GP at Laguna Seca in '89 but never made it to the podium. He ditched his bike in the dirt so he could rush to Shobert's aid. He missed the ceremony. Yes he was fined by the FIM.

The circumstances of, and the brawl over, third place eventually branded 1989 as the worst USGP ever. Late in the race, Rainey was out front, having almost effortlessly left the pack. Schwantz owned second place comfortably.

Third place, though, was a different matter, as three or four riders disputed the position for most of the race: Kevin Magee on the second Roberts Lucky Strike Yamaha, Lawson on the Kanemoto NSR Honda, Gardner on the factory NSR and even a distant Niall Mackienzie on the second Agostini Marlboro Yamaha.

Gardner left the fight for third in an ambulance after a wicked lap ten crash. Anyone who has tried to break a green tree branch in half can imagine what Gardner’s femur looked like post-crash, with the bone broken and twisted in two.

Hanoi Henny

The very last race of American Grand National and Superbike champion Bubba Shobert. Here he leads former AMA 250 champion Randy Mamola on the Cagiva at Laguna Seca in 1989. Shobert was riding an NSR500 sponsored by Cabin cigarettes.

Lawson had third place by the halfway mark, but even the steady one started to ride wide in corners when the piggish Honda’s chassis and brakes wheezed. You can’t ride anything but the precise inside racing line at Laguna and expect to do well. Lawson’s uncharacteristic wide line eventually let Australian Kevin Magee past, and with just a few laps left in the race, Magee appeared to have third place under his belt and an all-American podium was off the books.

Rainey rode a red-hot pace at the front, and the riders behind him pushed hard as well—so hard that they were lapping into the back half of the top ten as the laps slipped away.

Just one lap from the end, with Lawson behind him, watching, stalking, Magee’s Yamaha began to burble and pop, his fuel supply diminished. The Yamaha never ran out of gas, but it starved for fuel as the remaining pints in the tank splashed away from the petcock. The fraction of a second that Lawson needed to pass Magee appeared with a Christmas bow on it. He didn’t waste a tenth of a second passing the Yamaha and cementing third place. Rainey won the race—his first-ever USGP win, Kevin Schwantz was second and Eddie Lawson third. The all-Yankee podium actually would have happened, if what followed on the cool-off lap hadn’t.

Magee was enraged that his Yamaha had let him down and run low on fuel. Thus, on the cool-off lap, Magee stopped his machine in the middle of the racetrack to do several long, billowing brake-lock burnouts, taking out some of his frustration on his rear Dunlop slick.

Carnage

Kevin Magee did two or three burnouts in the turn five/six area of the track on the cool-off lap of the 1989 USGP, each a little longer than the previous. Magee parked almost dead-center on the track when doing so. Smoke billowed off the Dunlop and gave the backside of the track sort of a fog at dawn appearance. At the same time, inexplicably, after the aforementioned lapping and then post-race shuffle, third-place finisher Eddie Lawson had finished the race riding next to Bubba Shobert on the cool-off lap. They obviously weren’t racing, and were in fact sitting up, but after a guy has been racing at 170mph and his body is vibrating from adrenaline overload, even 100mph on the cool-off lap seems pathetically slow.

Shobert had just scored the best finish of his young GP season. He’d moved from Texas to Monterey and performed well in front of not just fans, but people who might have been his neighbors. He had a lot to be happy about, and not just for his own sake—his best friend, the man who he had stood with as best man at his wedding, Wayne Rainey, had won the race.

At some point, as Lawson and Shobert, side by side, rode up the track and through the wisps of smoke from Magee’s burnouts, Both old dirt trackers, Shobert looked right over at Lawson, their eyes met through the visors and they smiled at each other. “He sort of motioned to me, with three fingers, asking if I finished third. I nodded yes and put up three fingers,” remembers Lawson. “He was happy and he gave me the thumbs up and grabbed a big handful of throttle.” They were, naturally, near the center of the track, not far off the racing line.

At the last nana-second, out of the corner of his eye, Lawson saw something solid in front of them and he quickly counter-steered, slamming the clip-ons left to quickly swerve right. He narrowly missed Kevin Magee’s still smoke-spewing Yamaha.

Shobert was not as lucky.

Shobert’s Honda hit the back and side of Magee’s Yamaha at full impact; there wasn’t even a moment for Shobert to grab the brakes. “He was still looking at me until the last moment,” recalls Lawson today. “I don’t think he ever saw Magee’s bike through the smoke.”

Shobert torpedoed Magee’s machine and the two went careening up the track, bodies and bikes tumbling and sliding in a sickening scene. What moments before looked like a typical foggy morning in Northern California now looked like the morning-after scene from the film Platoon. People were screaming, tire smoke wisped in the air and smashed motorcycles and parts littered the area.

Lawson succinctly describes the post-incident scene: “It looked like a plane had crashed.”

Shobert lay motionless on the ground. Magee had tumbled off his bike but he crawled up, pulled off his helmet and walked back to the scene, limping badly from a now broken ankle.

Lawson rode off the track after the incident. He hoped Shobert might get up and need a ride back but knew in his gut what he had narrowly missed was bad, thus he slowed his Honda to walking speed and then quickly killed the engine and simultaneously dropped the bike on the ground. He sprinted back to the scene, his pace quickening as the horror he saw through his face shield came in focus.

Shobert lay face-down on the ground, unresponsive. His breathing was erratic and his color darkening. Lawson thought that perhaps the chin strap on Shobert’s Bell helmet was preventing him from breathing, and with the ambulance was still in turn two, he reached in and very carefully undid the strap, being implicitly careful not to move the Texan’s head or neck. Cornerworkers, fans and riders walked among the debris as ambulance sirens wailed on their way to the scene.

Kevin Magee stood in the middle of it all, fat tears streaming down his face; he tried to walk, hobbled by a now broken ankle. He would miss three Grand Prixs because of the injury and finish fifth in the world championship that season.

“I’ll never understand why he chose to do that right in the middle of the racetrack,” Lawson said.

Even years later Wayne Rainey can not remember the 1989 USGP for his breakthrough win at the racetrack near his home and closer to his heart. He confessed several times that if he ever lets his mind wander to the 1989 event, his first thoughts were not of his win, but of the tragedy involving his friend Bubba Shobert.

A year or so after the incident Shobert told me that he had no feelings of resentment for Magee or what had happened. He said that in the racing life some risks are accepted no matter how unfair they might seem after the fact.

Be that as it may, some members of the American contingent in Grand Prix didn’t let the incident simply drift away. Later Kevin Schwantz was teamed with Magee at Suzuki and he kept him at arms length the entire time. He wasnt unfriendly, but just did what the team expected him to do—smile for the photographer guys—and little more.

Kevin Magee and Eddie Lawson were involved in several on-track incidents that season and after one such episode, Lawson made his feelings clear on Magee’s ability to control a racing motorcycle, and his judgment in doing so. Lawson said Magee accused him of really being angry over the Shobert incident. “I told him no, ‘it’s just that you’re an idiot.”

“I’ll never understand why he chose to do that right in the middle of the racetrack,” Lawson said.

The USGP didn’t return to America in 1990.

Hanoi Henny

Future three-time world champion Rainey absolutely dominated the 1989 USGP at Laguna Seca. His mechanic, Mike Sinclair, had the 1989 YZR500's 35mm Mikuni flat slides tuned to perfection. Magee's YZR ran out of gas a few laps from the end and he had to back off and rock it to get it across the finish line. Rainey's bike went dry on the cool-off lap, just as they planned.

Back Story

"The 1989 YZR500 jetting was critical for the way I rode the bike that year, especially at Laguna Seca," Rainey explained via text message. "The initial throttle opening was key. It was critical for engine response at maximum pressure from the engine at whatever RPM it happened to be at ... plus, the pressure on the chassis and tires and how I applied the throttle with all those factors played an important role in producing fuel mileage to get me to the checkered flag and on two wheels. My bike surged at the top of the Corkscrew on the last lap." (Engines will surge when running very low on fuel when the air/fuel mixture is mostly air.)

If you have photos from the 1989 USGP at Laguna Seca, send them here: superbikeplanet@gmail.com

— ends —